Breaking gender norms: Women in coding

Considering the amount of technology we surround ourselves with and the time we spend online, it is safe to say that code plays a fundamental role in the world as we know it today. Even the simplest of tasks, like calling your mum, tapping your credit card, and watching a show on Netflix, are all connected to code. Although it is considered as an abstract concept by many, coding is a classic example of how rapidly human inventions can advance and progress. But what does the industry look like from a gender equality point of view?

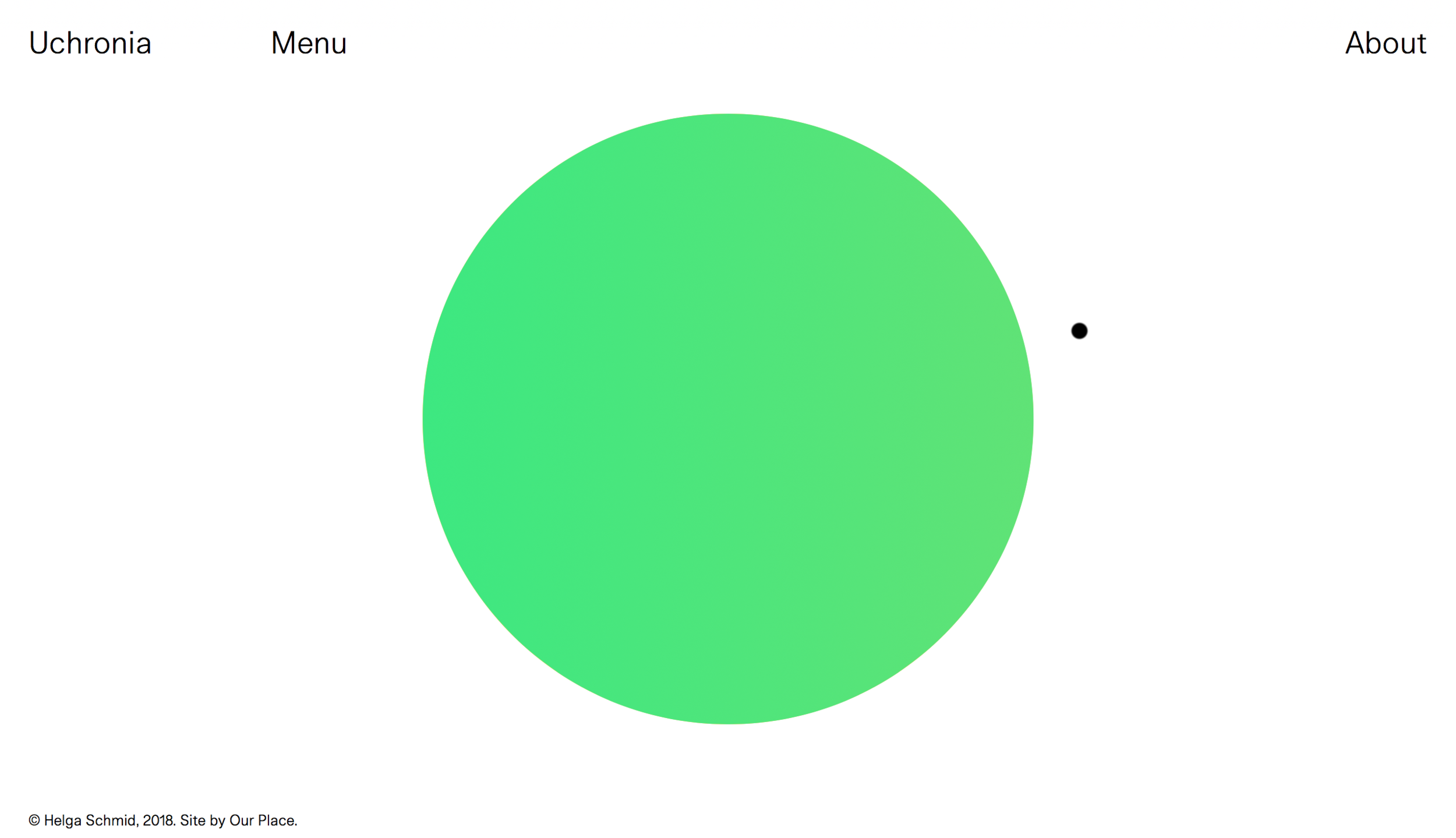

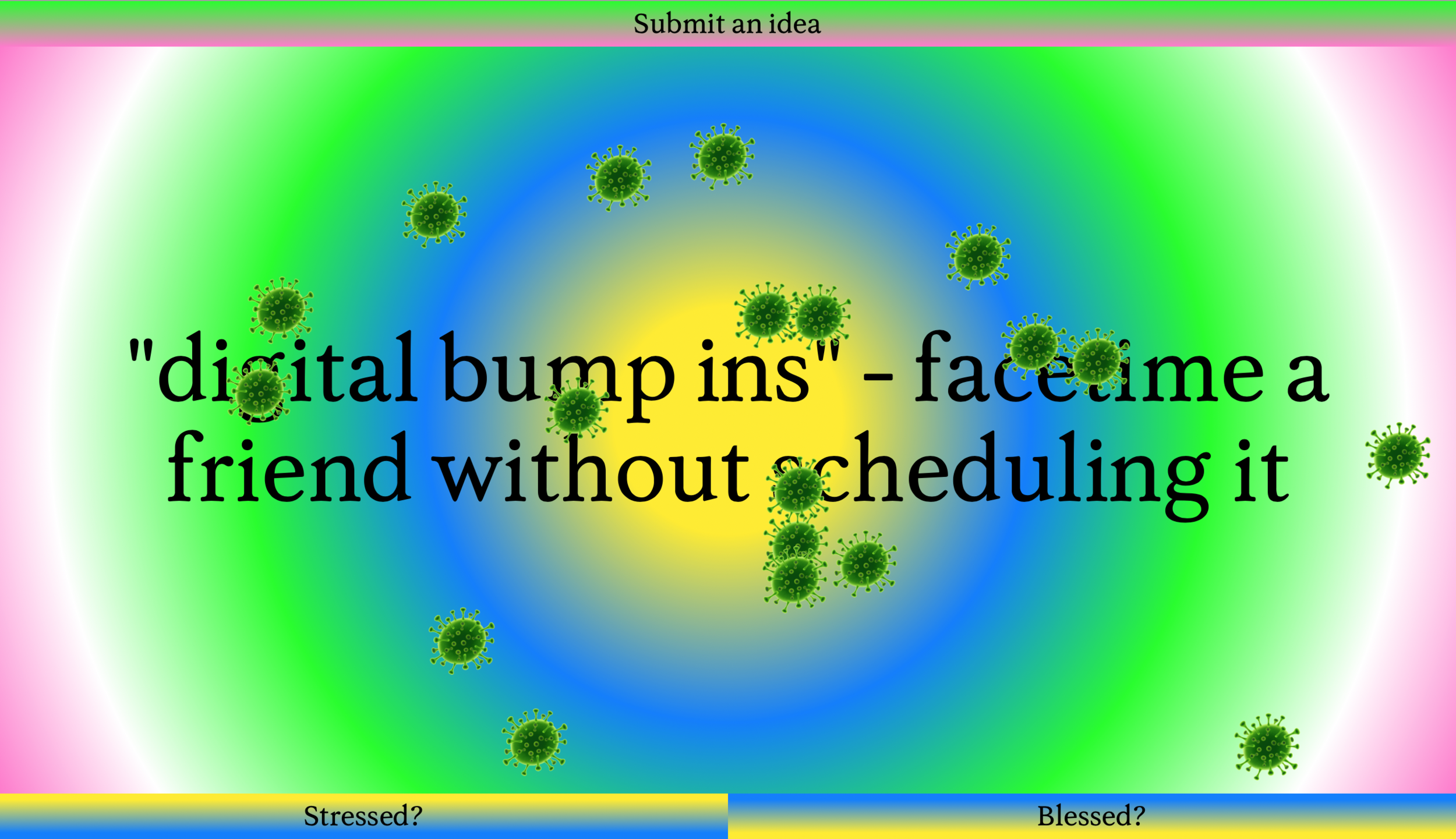

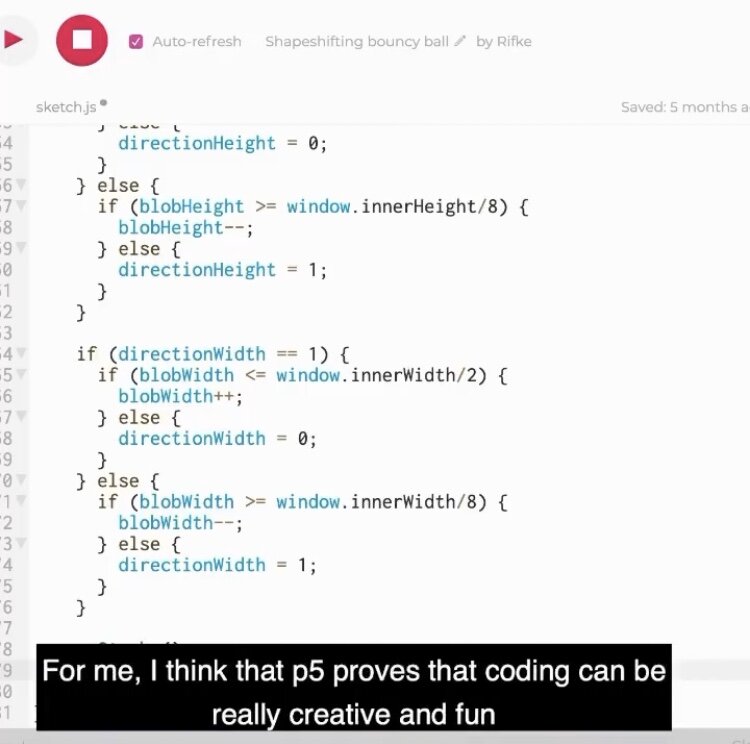

Meet Rifke Sadleir, a 26-year-old coder and web designer based in South East London, who’s personal style is characterized by bright and clashing colours and lots of animated features. Currently, she spends her time working as a creative developer and art director at DxR Zone a space shared with fellow creative Dan Bara. We had a chat with Rifke about what it is like to work in coding and being a woman in this industry today.

At university, Rifke was given the chance to learn to code in Processing, which she describes as a coding environment that enables artists and creatives to code without the steep learning curve. Her career in coding, however, started when a friend introduced her to Multiple States. “At this point I’d never written code for web, aside from changing the colour of text on my Tumblr account and things like that,” she says. Multiple States wanted to see if they could teach someone with no prior knowledge of how to build a website from scratch, which resulted in Rifke landing a week-long internship that turned into a part-time job.

Traditionally, coding is considered a “masculine” profession, and in similarity to other male-dominated fields, many women in coding have experienced prejudice because of their gender. In recent years, however, the importance of diversity has become a main priority for an increasing number of companies, leading to more opportunities for women and people of minority backgrounds than ever before. Luckily, Rifke says that she has faced less prejudice than people would expect from her line of work. Nonetheless, there are still the occasional exceptions: “The funniest one was when I went to a meeting with a client and we spent 10 minutes looking for each other, when we eventually did they admitted they’d been looking for a man the whole time,” she says.

In terms of encouragement, Rifke received support from both tutors and parents when she first took an interest in the world of coding. “My dad tried to teach me some HTML when I was about 11 and I was really unreceptive then so I think he’s glad I’ve finally cottoned on!” To this day, Rifke’s mum is the first person she goes to if she wants someone to test a website. “She always gives me a straightforward answer about whether it’s easy to use or not.” In similarity, her new interest was also welcomed at university. “My tutors were all graphic designers and visual artists but still showed an interest in what I was doing, but from a creative rather than a technical perspective.”

She points out that in the past, boys would receive more encouragement to pursue a career in coding than girls, but there have been made many conscious steps to bridge this divide since then. “I think there’s finally much more of a movement surrounding getting girls into coding, which is great!” she says. Rifke has taught various workshops and explains that, unsurprisingly, gender has nothing to do with your learning process in coding, finding the suggestion that one gender being more capable than the other to be ridiculous. While the traditional stereotype is that middle-aged, white men are coders, she says there has been a significant change of mindset when it comes to what a typical coder is expected to look like. “Students today don’t seem particularly predisposed to even contemplating, whereas this was a conversation coming up much more even five years ago when I was studying.”

Quotas are one of the efforts that are seen as an effective solution to imbalanced numbers of genders in the workplace. Despite it being a controversial practice, Rifke has turned more positive towards it in the past few years. “I occasionally get asked to do jobs because ‘we’re looking for a female coder’, and this used to really offend me—like, if I was a man would my code not be good enough? Are you hiring me for my gender instead of my work? While I continue to struggle with this a bit, I now understand the importance of being the person who’s brought in to diversify the team.” However, she believes there is a right and wrong way of using gender quotas, especially distancing herself from referring to the importance of avoiding tokenism. You should be viewed as equal to your counterparts, not merely a number on a sheet of paper. According to Rifke, the right way to use quotas, which is also the most productive, looks like this: “Your perspective and experience are listened to and used to shape the direction of the project to enable the finished thing to better represent and serve your demographic, which is a really valuable thing to bring to a workplace.”

In Rifke’s opinion, it is vital to encourage companies to actively work towards diversifying their workplace because technology takes so much from the personal experiences of its creators. “Technology is such a huge part of everyone’s lives, but if we’ve only got one narrow part of society building our tech, it’s inevitable that the technology they build will end up primarily serving their demographic and the issues faced by that demographic. That’s not to say that the people creating technology are malicious or bad, it’s more that it can be hard to step out of your own perspective and create something for people with different sets of experiences and needs.” Facial recognition technology is one of the many real-world examples that she points to. A lot of the algorithms are very accurate on white skin and features but much less so for black skin and features. In 2019, US government tests found that even top-performing facial recognition systems misidentify black people ‘at rates five to 10 times higher’ than they do white people. This illustrates the the crucial impact inclusivity in the workplace can have on the product a company produces.

While it is clear that prejudice against women in the coding industry has become less of an issue in recent years, companies still need to work actively towards giving everyone an equal opportunity to pursue their interest in coding. “I think the thing that initially attracted me to coding is the fact that unlike static design, the interactive design requires the user to actively participate in the work to bring meaning to it. I love seeing how work gets used once it’s made public,” Rifke says. Over time, she has also seen her work impacting her daily life: “I feel like it’s made me more persistent because coding is a process of ‘two steps forward, one step back’ a lot of the time.” In other words, the world of coding is an interesting industry to take part in as a creative today, but it needs to continue to strive to be a space in which everyone feel welcome regardless of their gender and background.

Illustration by Zsófi Mayer.

Photo credit: Websites developed by Rifke + collab with @instituteofcoding.

Related content

Interview with professional chess player Nomin-Edene Davaadembrel about being a woman in a male-dominated sport

The alphabet of what women don’t owe you, have to or need to.

The pressure to be what society deems as "perfect" is too easily inflicted on young and impressionable girls, especially when the pressure seems to be coming from everywhere.

Seven women talk women’s empowerment and role models.